Someone asked me recently to explain what INQUIRING DEEPLY was and how I came to be interested in it. Answering these questions, I was able to see the long arc of the path of awareness practice I have been following since I was a young child.

Inquiry in spiritual practice is the process of asking ourselves deep questions about the nature of our existence: questions such as “WHO AM I?” or “WHAT IS REAL?” In contrast with spiritual inquiry, INQUIRING DEEPLY begins with exploring the painful psychological dramas and stories in the psychological world of lived experience. Its fundamental assumption is that wisdom is inherent in whatever is arising, dual and non-dual experience alike [i], and that we can open to that wisdom through investigation and inquiry.

The stories that we tell— about ourselves, about others, and about what we consider to be real— comprise the system of meaning in which we live. In my view, not only are these stories not “beside the point”, as Buddhist teachings often suggest, they are vital to self-understanding. As writer David Loy puts it, our world is made of stories.[ii]

INQUIRING DEEPLY came about in me in response to my efforts to create a conceptual “home” which would honor both my psychodynamic and spiritual interests. Self-reflective and philosophical by nature, I have “inquired deeply” as the natural expression of my being throughout my lifetime. The long version of my personal story about INQUIRING DEEPLY need not be repeated here, except to quote my own punchline, which was, “inquiring deeply is me.” (The joke, in case it is not obvious, is that seeing through identification with “me” is the entire point of inquiry practice!)

The autobiographical flavor of INQUIRING DEEPLY is conveyed by the following early memories that come to mind:

- I am about two years old and I am standing in the sunshine, aware for the first time I can remember that I am aware. I think of this moment as my birth into self-reflective awareness. (A photograph taken of me in that moment has always been in my possession, so perhaps that image is what framed the significance of that particular moment.)

- I am sitting on the sandy bottom of a beautiful brook in Connecticut, with my head beneath the surface of the water. I am three years old. I have a stone in each hand and I am clinking them together, deeply fascinated by the way the sound reverberates in my ears. I am in a state of consciousness in which there seems to be little need to breathe.

- I am sitting on the bed in the bedroom of my childhood, looking out the window. There is a diamond-shaped metal grating/ guardrail on the window and as I gaze out with soft focus, the diamond pattern telescopes out and expands into a deep three-dimensional space. The experience is compelling. I repeat it often.

- Not yet five years old, I wonder often where I was before I was born.

When I told these experiences to a meditation teacher many years later, he told me that I had been a Zen child! Be that as it may, these memories are emblematic of many similar experiences which informed my life and set me on the path of awareness practice. What I yearned for was the expansive freedom that seemed inherent in these altered states of consciousness.

Apart from its autobiographical roots, what seems most important to say about the origin of INQUIRING DEEPLY is that it emerged in me. I often liken inquiry to an extended ‘conversation’ that takes place both within myself and in the external world simultaneously. And, just as we may often have no idea what we will say until we open our mouths to say it, it often seemed to me that insights emerged unbidden— arising in response to unseen forces or through synchronous events. When this happens, it feels to me as though life is alive and responsive to my questions, and that answers are called forth by my intention to find them.

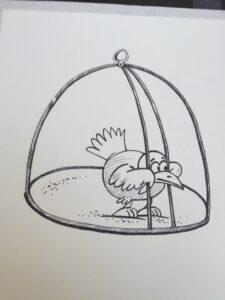

The cartoon in the header, originally entitled “The Human Condition”, is a good example of an emergent answer. It was passed along to me by a friend at a time when I had hit an impasse in a paper I was writing about spiritual seeking. For my purposes at that time I changed the caption to “to free the spirit from its cell.” [iii] The cartoon expressed better than words what I had been struggling to say: (1) our spiritual predicament is that we fail to recognize that the freedom we seek is already present; and (2) the realization we seek is often impeded by our own limiting assumptions, views, and beliefs.

Contemplating the picture of the bird in its cage while writing these words, it occurred to me to inquire deeply: “what have I held onto that has kept me trapped in ordinary states of consciousness?”

The first answer that occurred to me was how hard I have tended to work at my spiritual practice. My character is such that I hold tight to my need to know! Given the way my mind is organized around knowing, wise effort—not too tight, not too loose— has been challenging for me.

Next, I saw that I had regarded “ordinary states of consciousness” as a booby prize in meditation practice. I was always striving to recreate the expansive experiences I had heard about or read about in spiritual literature and which had spontaneously occurred when I was a child. This pursuit of peak experiences was in the way of my simply being with things as they actually were.

On yet another level, I held to the belief that in order to attain “higher states” I needed to change or fix something about my mind and that this fix involved more thinking and/or doing. Identifying with being the Do-er was definitely not helpful to my spiritual quest!

Eventually, I came to relinquish looking for transcendence in meditation in favor of a simple preference to relax/receive/ and allow whatever was unfolding in my experience. As I meditated in this receptive way, I found my awareness increasingly drawn into a state of deep inner silence, and I saw for myself that access to inner freedom was based in this embodied experience of relaxation and letting go. I learned to put my attention on the background field of awareness from which experience continually arises and disappears.

I have called INQUIRING DEEPLY the path of “practicing with problems” because I found that my problems often seemed to be the leading edge of change in my life. Analogous to the role of pain in the body, problems always seemed to point me toward I most needed to see. [iv] For example, during the time that I was writing my 2023 book about problems [v] I went through a period of very familiar agita that often shows up when I am writing. The agita, itself, has long lived in my mind as a multifaceted “problem”. It is a rather uncomfortable experience which “I do not prefer”, to borrow an understated phrase from a good friend of mine. In the midst of inquiring deeply about it, an important “aha moment” occurred: I recognized that the problem was the problem!

I came to regard this insight as an inquiry unto itself; (or, as a Zen practitioner might say, as a koan.) There is no such “thing” as a problem! “Problem” is a label or a concept we put on something we would rather not have to deal with; something that we would prefer to make disappear. But once you recognize that a “problem” doesn’t connote that something is wrong, the entire situation is poised to turn upside down. Now, “problem” means, instead, something needs attention; or something needs to be better understood. It is a process: “probleming”.

What most of us tend to do when encountering a problem is to try to figure out what caused it and what to do about it or how to make it go away. Instead, Inquiring Deeply changes problems into valuable (and ineluctable) opportunities for awareness practice. And, in that space of deep inner listening, insight and breakthrough often emerge.

Coming full circle now, INQUIRING DEEPLY unfolded organically in my life as a function of many moments of insight that came about as I followed along in the slipstream of my awareness and curiosity about problems. I came to believe that there is a subjective intelligence in life that I can access by dropping down into experience and allowing it to reveal itself. Inquiring Deeply creates a kind of radical openness in which we may be able to see where we have shut down, where we need to wake up, and where we need to grow—and, in special moments, it may free our spirit from its cell.

***********************************************************************************************************************************

[i] “Dual experience” refers to the ordinary perception of reality as consisting of subjects and objects, whereas “non-dual experience” is the perception of a unified reality where there is no separation between self and other, essentially experiencing everything as interconnected and one whole.

[ii] Loy, David (2010) The World Is Made of Stories. Wisdom Publications, Somerville, MA.

[iii] I borrowed this phrase from a paper written by the well known psychoanalyst, Bernard Brandschaft (2010). In Brandschaft, B. (2010) Towards an emancipatory psychoanalysis: Brandschaft’s intersubjective vision. Routledge Press, New York.

[iv] Schuman, M. (2023) ) Inquiring Deeply: Problems as a Path to Awareness. Inquiring Deeply Press, Santa Barbara, CA.