The psychological and mental health consequences of the COVID pandemic have been a popular focus of many recent television interviews, magazine articles, and dharma talks. In my previous newsletter, I described one aspect of the emotional impact which I termed “existential shock”: a kind of radical and fundamental wave of turbulence in the collective psyche. Existential shock happens when we have been confronted with the truth that Reality is always and irrevocably tenuous and uncertain. The “normal” we return to may or may not be very similar to the one that was left behind.

Apart from existential threats of illness, death, and loss (including financial insecurities), quarantine provides its own set of emotional challenges. While the particular obstacles vary with individual circumstances, what we can notice is that sheltering at home is far more disruptive for some people than others. We depend on the quality of our interaction with others in order to be able to effectively manage our feelings. Being too alone and deprived of ordinary channels of social support can be difficult, to say the least. And, conversely, being cooped up with others who may themselves be emotionally off-balance can be triggering. For these reasons, quarantine can push us into the deep water of ourselves.

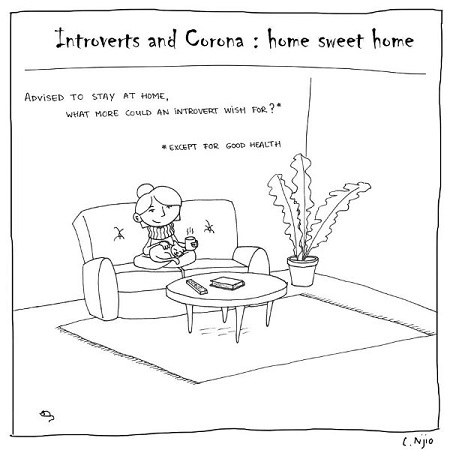

What I notice in my psychotherapeutic work with others is the truth of the aphorism that wherever you go, there you are. Our experience of quarantine— of any experience—depends not only on our circumstances but also upon both our temperaments as well as our different histories and experiences of “home” and “family ”. As depicted in the cartoon, what is an imprisoning isolation for one person may feel like a cozy cocoon to another.

For those of us who are introverts and/or homebodies, the experience of quarantine may feel congruent with a preferred way of being. For example, sheltering in place can provide permission to “hang out” in the rhythm of the day; a slower pace of life that is more stay-cation than isolation. But we can also notice that aloneness does not always feel the same. It can feel very full at times, empty or lonely at others. [What is the felt sense of a companionable aloneness with yourself? In what ways do you tend to get lost in distractions, avoidance, or spacing out? ] .

The other major dimension of quarantine, “social distancing”, gives us an opportunity to investigate the surface of our connection with others. What internal experience spurs the impulse to connect? What are we hoping to get? (Comfort? Validation? Stimulation? Distraction from an unpleasant internal state? ) What defines the difference between a satisfactory and an unsatisfactory contact with someone else? Do we get energy from connection, or does it drain us?

“Introversion” is not a one-size fits all personality trait nor even a particular relational style. It is not simply the preference for spending time alone, the tendency to be quiet, nor social reserve. It is a complex mixture of our experiences of being alone and our ways of being with others. It is possible to feel quite connected socially even when we spending time by ourselves. And conversely, it is also possible to feel more alone, or even lonely, when we are in the presence of others.

What we can discover when we inquire deeply about our experiences of introversion and social distancing is that our connection with ourselves and the interconnection between ourselves and the world are two sides of a single coin.