Wise Relationship Part IV: Irreconcilable Differences

Wise Relationship, Part IV

Irreconcilable Differences

Generally speaking, we seek agreement with our significant others, but differences are inevitable. In the interest of “wise relationship”, it behooves us to understand what constitutes “irreconcilable differences” and how best to relate to them.

In simple terms, I define an “irreconcilable difference” as any interpersonal issue which puts the viability of the relationship in question– something which causes intractable conflict and for which no solution can be found. But when we look closely at such situations, often we find that the issue is less about the substance of the difference than it is about how both people are reacting to one another. Beyond the content of so-called irreconcilable differences, there is generally something about the other that each is unable to accept. It is wise to look beyond the disagreement to the reactive process underneath.

In previous issues of this Newsletter, I unpacked some aspects of our reactions that are due to the complex web of psychological/emotional/relational conflicts that I call entanglements. Here I want to focus on the nature of differences in values, opinions, and beliefs; to differences in subjective “truth”.

Of course, how we relate to our differences is as much about our psychological and emotional patterns as it is about our points of view. We have very different “windows of tolerance” for differences. In one couple I worked with, for example, different tastes in music and preference for how loud music should be played in their home had become a domestic war. Recently I have worked with several couples struggling to middle ground between troubling differences in political views. In seeking to help couples work through disagreements, I try to help them see clearly where they are stuck and what is at stake for each of them.

The crux of the matter often seems to boil down to a conflict over whose view is right and whose view is wrong. All of us tend to assume (and prefer to think) that our views are correct, and we get very invested in our positions about things. After all, our views construct the reality we live in, and the need for reality to be coherent is a primary psychological need. In such situations, it is useful to see clearly what it is we are trying to be right about and why that is important to us. It is also useful to look for instances of black and white thinking. Both/And is a much wiser frame than Either/Or!

Polarized disagreements often devolve into fights which involve negative judgment and blame– basic manifestations of anger. In examining this relational pattern closely in many couples, what I have invariably found is that someone, or both someones, are certain that they are right. The attitude of moral superiority that creeps into such disagreements is one of the most common emotional stumbling blocks between significant others.

For me, as I think for many of us, an attitude of righteousness in others is one of the most difficult personality characteristics to be with. There is value in inquiring deeply about this until we begin to discern clearly the shadow of the same righteousness within ourselves. The need to be right is a basic aspect of the way we defend cherished views of ourselves; views that we are very identified with and invested in.

In considering how to respond wisely to disagreements with others, I have also found it valuable to reflect on a quote attributed to the film director Federico Fellini: “happiness is being able to tell the truth without hurting anyone.” What “truth” is it that we think we need to tell?

As a preliminary step, we are wise to understand that what we consider to be “the truth” is subjectively determined and therefore necessarily subject to disagreement. One of the basic things that I have learned in working with people in psychotherapy is that, regardless of its objective validity, subjective truth needs to be understood/validated. If we look deeply enough, what we can find is that everyone has good and sufficient reasons for taking the positions that they do; for their behavior and for their beliefs. Right vs. wrong is a very limiting frame. However, that does not mean that we should regard all truths as equally valid. There are outer limits to what points of view we can regard as sane, and our respect for the reality of others will necessarily be constrained by what we consider to be crazy (or even dangerous). Nonetheless, communication is well served in any conflict by the sincere intention to see and empathize with the other’s point of view.

Another basic observation is that hearing our truth will feel uncomfortable to someone who doesn’t wish to accept it. Beyond the need to be right, we all want to maintain a positive view of ourselves, and it can be painful to take in the negative view that someone else may hold. But notwithstanding that criticism may be painful for someone to hear, it also provides an important opportunity. (In the vernacular, an “AFGO” – another f-cking growth opportunity !)

Consider, moreover, that there is risk in not speaking my truth as well as in speaking it. For though it may hurt you for me to tell you my truth about you, it may also be unwise for me to protect your feelings at the expense of abdicating my own.

A good general strategy when we find ourselves in intractable conflict with another is to back off as much as necessary to restore (or find anew) the “highest common ground”. At the intersection of our differences, it is also helpful to practice what I have called elsewhere the “intimate dance of speaking and listening”[i]. Beyond cultivating communication skills, deep listening is a way to deepen the intimacy of our interaction and invite the unfolding of a mutual experience of being known. Beneath the surface of conflict, there is a lot we can learn about the common humanity of our vulnerability; of our wishes and fears to be seen and heard and to connect deeply with others.

If, as Fellini suggests, happiness is being able to tell the truth, we also need to recognize that wise relationship entails not just speaking but living your subjective truth. “Should I leave?” is an important question, and living in the question of whether our differences are irreconcilable is a complex challenge. ‘Irreconcilable differences’ are a way-station that may arise on the path that people sometimes travel when they are seeking to emancipate themselves from bonds with others which they find to be shackling. However, as Buddhist teacher and psychologist Jack Kornfield reminds us, while it may feel necessary to distance ourselves from another person for awhile or forever, it is never necessary to put anyone out of our hearts. In other words, we don’t need to use irreconcilable differences to justify our need to separate.

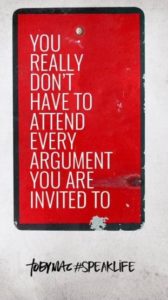

Instead, wise relationship invites us to speak, act, and live our lives, not from reactive patterns, but from the “wisdom inside the growing capacity to pause, reflect, and connect with choice” [ii]. While we may not be able to resolve a disagreement, we can usually find a way to reconcile by appropriately adjusting our boundaries and interpersonal distance. The quality of our relationships rests upon the foundation of our wise understanding and the kindness of our intentions.

[i] Schuman (2018) Speaking and Listening: The Intimate Dance of Speaking and Communicating. Wise Brain Bulletin, 12(5).

[ii] Redding, K. (2022) Ten Qualities of a Wise Heart. Creative Press, Anaheim, CA